A landmark event in medicine was reported this week that has implications well beyond its likelihood of saving a baby’s life. Until now, commercially available CRISPR genome editing (Casgevy) was not capable of directly fixing a genomic defect. It was a workaround plan, that can be regarded as CRISPR 1.0. In this edition of Ground Truths, I’m going to take you through the advances in genome editing and why the new case report at NEJM heralds an extraordinary opportunity for the future of medicine.

What Is CRISPR 1.0?

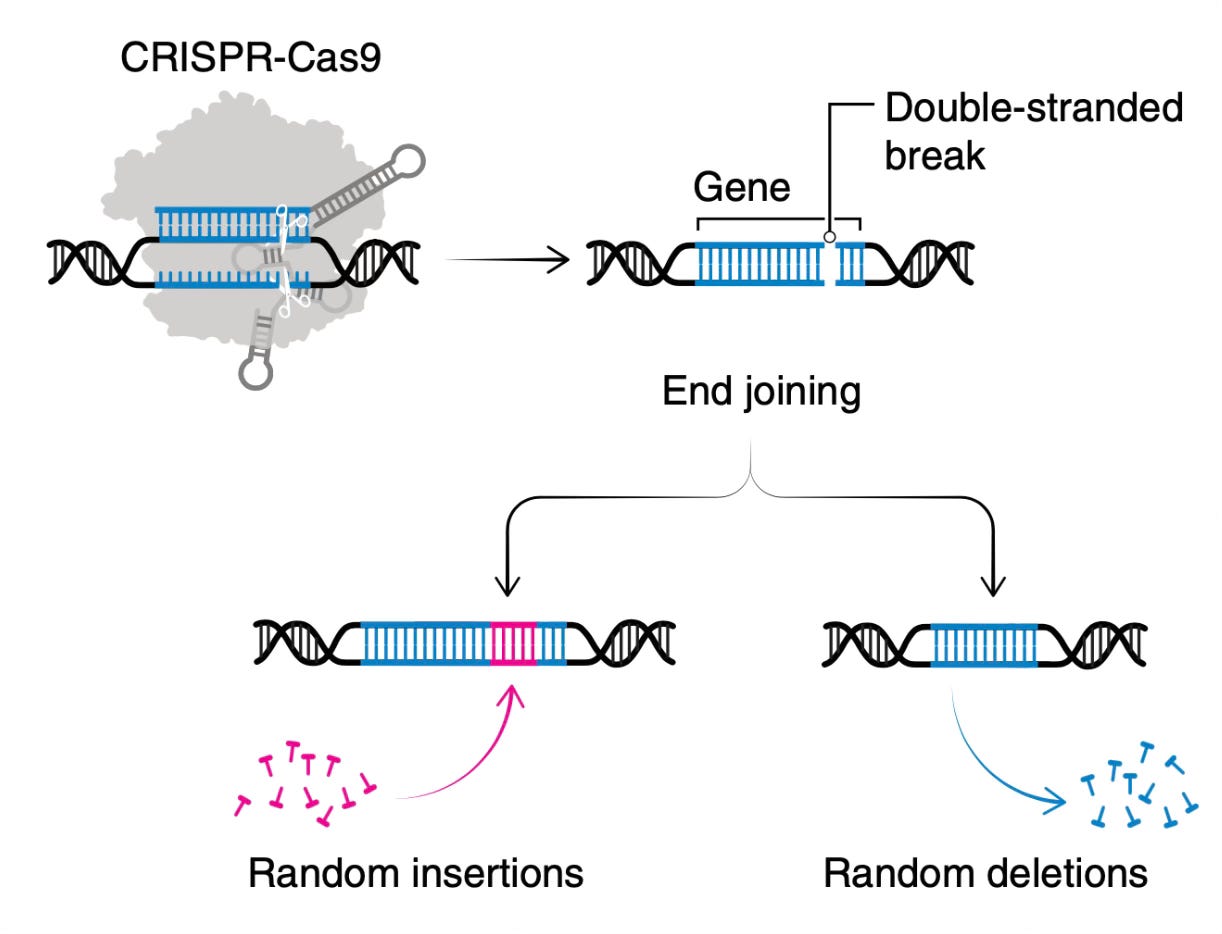

This is the type of genome editing that led to regulatory approvals for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia in late 2023, after a decade or research. It relies on making a double-strand break in DNA, as shown below, cutting it into 2 pieces. When that occurs the cell wants to repair the chromosome broken ends. But that leaves a small percentage of mistakes in the repair process of rejoining. The Cas 9 nuclease keeps cutting and more mistakes accumulate. Ultimately, the gene is disrupted when Cas9 can no longer recognize the mistake-laden sequence pf insertions and deletions. This is a disruptive knockout strategy that doesn’t fix a gene. That works for sickle cell disease and beta-thalassemia because the disruption targets a gene called BCL11A (that turns off fetal hemoglobin production) to restore fetal hemoglobin production instead of actually fixing the defect in the hemoglobin gene. The editing is done ex vivo—outside the patient’s body.

That lack of fixing also sets the stage for a very complicated treatment course. The individual has to undergo a collection process of blood-producing stem cells that requires being connected to an apharesis machine for several hours, getting multiple transfusions, then chemotherapy to wipe out the bone marrow. This leads to a precipitous drop in white blood cells and requires hospitalization for weeks or months, under sterile conditions. Ultimately, the edited blood stem cells are infused but the patients is stuck in the hospital until the immune system recovers. Sounds grueling, very expensive, and complicated? Yes, it sure is.

Moving Forward with CRISPR 2.0

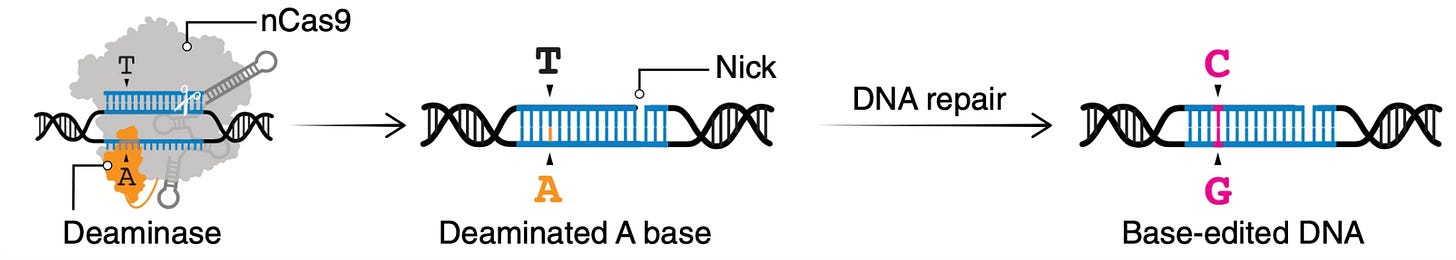

Instead of a double-strand break, base editing (pioneered by David Liu and colleagues, and discussed in our podcast) creates a single-strand nick (Figure below from Wang et al) and sets up a precise single base pair substitution, such as changing A's into G's G's into A's T's into C's or C's into T's. This constitutes directly fixing of the defect by doing chemistry of an individual’s DNA base.

Base editors were used in the new report, as we’ll get into. They are great for certain single base pair substations, but not all. There is another methodology called prime editing that is more versatile, capable of changing an A to a T or insertions of multiple missing letters like CTT, the most common genomic basis for cystic fibrosis. It is regarded as CRISPR 3.0. For more depth on the different editors, this is a very good review paper in Cell.

The first case of base editing that received much attention was done on T cells ex vivo for a 13-year-old girl with leukemia. Base editors have also been used in the body (in vivo) for familial hypercholesterolemia (but not individualized by the recipient’s genomics) and more recently (March 2025) for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. A different approach from base editing (called ARCUS, which uses a viral vector for delivery) was used for another urea cycle disorder.

The New Report

This was unique in many respects. KJ Muldoon was born in August 2024 with lethargy, rigid muscles and other worrisome symptoms. Genome sequencing revealed this was due to a severe urea-cycle disorder that leads to accumulation of ammonia and death in about half of infants affected, and short of death, the high levels of ammonia cause lethargy, seizures, coma, and brain damage. The disease-causing gene was CPS1 (carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase 1 deficiency), a 1 in a 1.3 million births genetic (ultra-rare) disease. KJ was hospitalized and awaited a liver transplant, listed at 5 month of age, if a donor organ became available. In the meantime, therapy consisted of a low protein diet and ammonia lowering (“nitrogen scavenger”) medications.

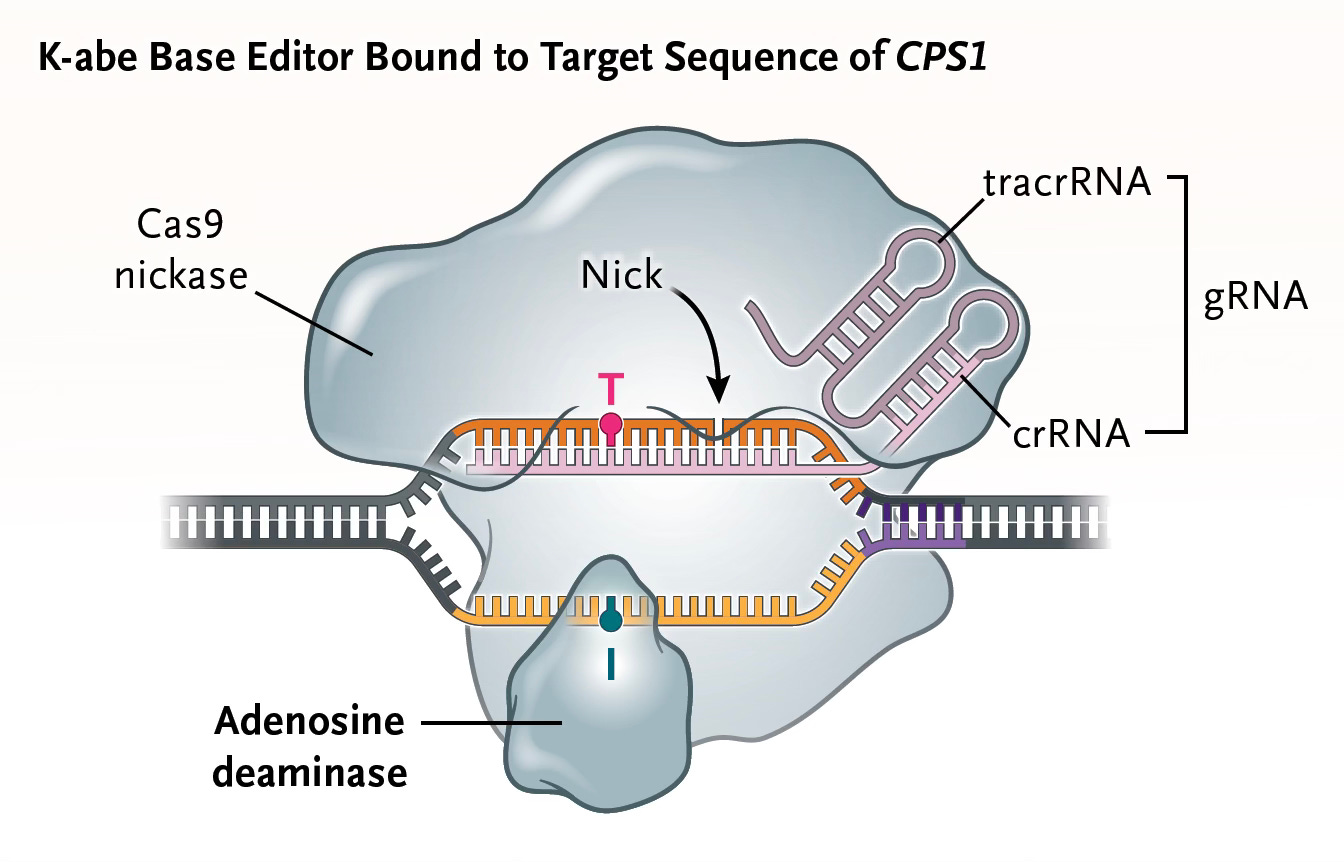

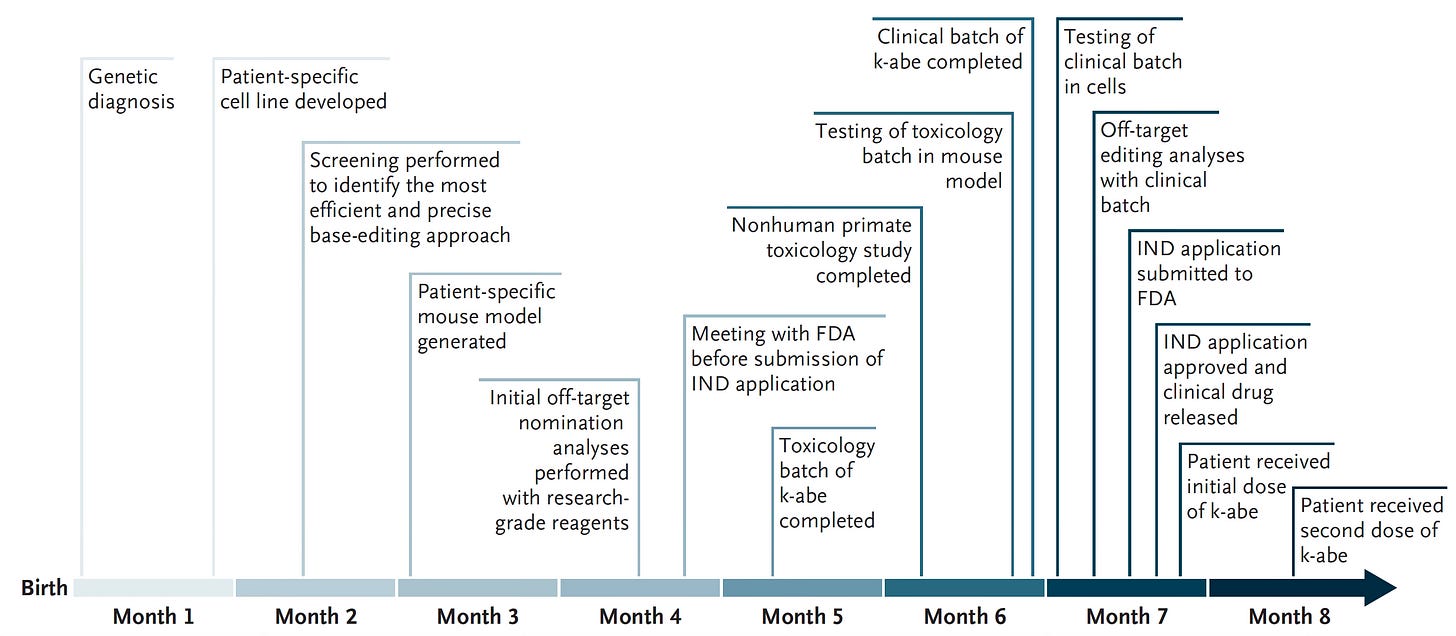

To get to the basis of KJ’s genomic defect and attempt a cure, the team at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and Penn Medicine (led by Drs. Rebecca Ahrens-Nicklas and Kiran Musunuru) sequenced KJ and his parents. The father had a truncating CSP1 variant (Q335X) and the mother a different variant, E714X). They developed an adenosine base editor (called K-abe, schematic below) to specifically correct KJ’s defective CPS1 gene. The approach taken was particularly rigorous and comprehensive. Within 6 months they tested the editor in cells with the genomic variants, in mice (bred to specifically have KJ’s CPS1 mutation), in non-human primates, and got FDA approval to give it. It was administered intravenously using delivery via mRNA + nanoparticles beginning in February 2025 and then with 2 subsequent doses. The base editor used was directed against the paternal mutation (a G→A stop variant) at the Q335X site of the CSP1 gene.

Dosing started at ultra-low and the first showed little efficacy as reflected by plasma ammonia levels. The second dose was ~3 weeks later and the third dose (not reported in the NEJM paper) was in April, just ~2 weeks ago. These showed signs of clinical benefit (vida infra).

The compressed timeline for achieving all this work was unprecedented!

What is missing to date is a liver biopsy, due to risk to the infant, to prove the targeted CSP1 editing. There is also lacking evidence of a cure—”just” a reduced need for medications and the restrictive diet. But also encouraging is that KJ is now reaching developmental milestones and although he sustained two viral infections, both were without an ammonia crisis. Further doses of the base editor can be administered with the mRNA approach (rather than a virus vector that can induce an immune response). Regarding uncertainties, we also don’t know about the durability of the editing, any mosaicism impact (only some liver cells edited), and the potential of any off-target effects (rigorously assessed in the 6-months sprint of lab experiments but not yet in KJ).

Concluding Remarks

This case of KJ represents a human first—-personalized, N-of-1 genomic intervention with base editing (CRISPR 2.0), in the body (in vivo), to directly fix a pathogenic (disease-causing) gene mutation. This bespoke intervention was accomplished in a remarkably compressed timeline that included rigorous assessment in cell and animal models, along with regulatory approval to proceed. It embodies something in medicine we have not and could not have done previously. It involved a dedicated team at CHOP and Penn and collaborators spread out around the world.

There are many specific aspects of the case that deserve attention. The fact that this work culminated from many years of NIH supported research, including the current report, at a time when we’re seeing profound and indiscriminate cutting of such funds

Related to that is the use of the mRNA-nanoparticle package for delivery of the intervention that is also being subject to cuts in funding at NIH without basis, no less potential lack of support by FDA, tied into misguided concerns about the Covid shots that saved the lives of over 30 million people. The mRNA delivery platform is also being used for developing vaccines for infectious pathogens for which there is no vaccine, for the genome editing programs, for cancer vaccines that have been successful for treating intractable cancers (neoantigen vaccines for both pancreatic cancer and renal cell carcinoma have been reported with a striking reponse in a limited number of patients).

We don’t know the actual cost of KJ’s genome editing, but had he gone onto a liver transplant it would likely have exceeded what this project cumulatively cost, and was supported by in kind contributions from multiple companies including Danaher, Aldevron Biosciences, Acuitas Therapeutics, and Integrated DNA Technologies.

The most important takeaway is that we have a new way of approaching rare disease with base and prime editors which account for ~90% of disease causing genetic mutations. Recall that there are about 10 thousand genetic rare diseases affecting ~6% of the world’s population, or about 400 million people. The overall global burden of rare and ultra-rare genetic diseases is huge, Were the approach pioneered in this case report made scalable, less expensive, and practical, imagine how many people could benefit.

Indeed, we are likely to see such scalability in the future. Many of the steps along the way here could be streamlined, some even omitted, such that this case be considered a template for the future. While today we can only approach diseases based in the liver, and potentially by intrathecal delivery into the brain, or outside the body editing T cells (or other cells), there is arduous work to improve the breadth of in vivo delivery to other vital organs. The Innovative Genomics Institute at UC Berkeley is orchestrating such streamlining efforts along with expanding targets to the lung, muscle and spine (the latter to achieve control of pain). Genomic editing in utero has also started.

There is another reason that this case is so important. Many rare diseases share common threads with common diseases. In my new book SUPER AGERS, which hit the NYT bestseller list this week, I explain how fixing the rare genetic defect of familial hypercholesterolemia with base editing, which is being undertaken by Verve Therapeutics, could be the basis of a one-shot treatment to prevent heart disease someday in the future. There is already preliminary work ongoing for prevention of Alzheimer’s disease with gene therapy of the APOE allele in people with two copies of APOE4, carrying a very high risk for the disease. And there are many other examples for how such advances for a rare disease could ultimately transform our approaches for important common diseases. It will take time, but I hope this post transmits the promise and excitement that lies ahead.

****************************************************

A quick poll

Thanks for reading and subscribing to Ground Truths.

If you found this interesting please share it!

That makes the work involved in putting these together especially worthwhile.

All content on Ground Truths— newsletters, analyses, and podcasts—is free, open-access.

Paid subscriptions are voluntary and all proceeds from them go to support Scripps Research. They do allow for posting comments and questions, which I do my best to respond to. Please don't hesitate to post comments and give me feedback. Many thanks to those who have contributed—they have greatly helped fund our summer internship programs for the past two years.

The scene in Kyiv earlier this month recalled the darkest days of oligarchic rule. U.S. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent slipped a piece of paper across the table to Volodmyr Zelensky. “You really need to sign this,” Bessent told the Ukrainian president, according to The Wall Street Journal. The document was a deal to give the United States the rights to hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of Ukraine’s minerals. When Zelensky said that he needed time to consider the proposal, Bessent pushed the paper closer to him and warned that “people back in Washington” would be very upset.

The Trump administration was operating in the old spirit of the kleptocrats who built fortunes in Ukraine and Russia at the dawn of the post-Communist era, wielding veiled threats to bully the nation’s leader into hastily handing over precious resources in a shady deal.

To Zelensky’s credit, he did his best to resist Bessent’s pressure. “I can’t sell our state,” he explained. It was as if he had actually internalized the message that American diplomats from the Bush, Obama, and Biden administrations had attempted to drum into Ukraine’s collective psyche: Ukraine’s democracy depends on it resisting powerful business interests that seek to plunder its wealth on terms highly unfavorable to the Ukrainian public. Zelensky’s willingness to stand up to President Donald Trump, holding true to American values in the face of American intimidation, was a perverse trading of places.

[Anne Applebaum: The end of the postwar world]

The moment recalls another episode in Ukraine’s recent past. Three years ago today, Russian troops streamed across the nation’s borders, assassins descended on the capital in search of its president, citizens decamped to the subways in search of shelter. Western intelligence agencies predicted Ukraine’s imminent demise. And in that moment of despair, Zelensky strode out into the empty streets of Kyiv, in the dark of night, to record a video reassuring the world, “We are still here.”

In those initial days of the war, Zelensky began to pose as a defender of liberalism, fighting on behalf of global democracy. Whether he actually meant it wasn’t clear. Before the war, his record of curbing corruption was spotty at best. With his political inexperience, and his strange unwillingness to prepare his country against the looming Russian threat, the former comic actor hardly had the makings of a sturdy bulwark against autocracy.

But he became one in the face of an unrelenting assault. Having preserved his nation’s independence, however, he’s now facing not one but two of the world’s most powerful illiberal leaders, conspiring in tandem. For reasons both petty and pecuniary, Trump seems intent on fulfilling Russian President Vladimir Putin’s goal of crushing Ukrainian sovereignty. The American president is pressing for Russia’s favored resolution to the war, without even allowing Zelensky a seat at the negotiating table. And the resource deal he’s pursuing amounts to World War I–style reparations, but extracted from the victim of aggression. It would force the Ukrainians to hand over the wealth beneath their ground, without any guarantee of their security in exchange. The extortion that Trump proposes would deny Ukraine any possibility of recovering economically, and consign its people to a state of servitude.

[Peter Wehner: MAGA has found a new model]

In this new moment of crisis, Zelensky is reverting to the role he played in the war’s earliest days. Confronted with blunt force, he’s bravely resisting. Squaring up to the bully, he accused Trump of swimming in disinformation. Despite all the pressure the United States has applied on him to accede to the mineral deal, he’s refused. Yesterday, he said, “I am not signing something that ten generations of Ukrainians will have to repay.” Knowing that Trump will never set aside his personal animosity toward him, he offered to resign in exchange for a Western security guarantee.

He has resisted the administration’s demands despite the fact that he has no leverage in his dealings with the U.S. other than moral suasion and a limited ability to get in Trump’s way. Ukraine’s military is entirely dependent on American arms, and its European allies can do almost nothing, at this late date, to fill the void. In the end, given Ukraine’s tenuous existence, Zelensky might have little choice but to accept whatever Trump imposes, but at least he’s shown that there’s a course other than immediate surrender.

[Quico Toro: Brazil stood up for its democracy. Why didn’t the United States?]

Once upon a time, the United States poured diplomatic resources and military aid into Ukraine so that it wouldn’t descend into Russian-style autocracy. Now it’s the United States that’s headed in that direction. In the form of Elon Musk, an oligarch has captured the power of the American government, through which he can invisibly advance his own interests. The president is attempting to intimidate (and sue) the media into complying with the administration’s agenda. The norms of the administrative state have been shattered so that Trump can reward cronies and punish enemies. And in the most literal sense, the United States is collaborating with Russian autocracy so that the foreign policies of the two regimes are more closely aligned.

American institutions have largely faltered amid Trump’s assault, and European allies have aimlessly panicked. But Zelensky’s very presence reprimands the West for its futile opposition; his resoluteness shames Republicans, who once admired him as a latter-day Winston Churchill, for their own abject capitulation. Although he arguably has more to lose from a Trump administration than anyone on the planet, he’s kept pushing back, with resourcefulness that recalls Ukraine’s guerrilla tactics immediately after the Russian invasion. When the history of the era is written, Zelensky will be seen as the global leader of the anti-authoritarian resistance, who refused to accept the terms that the powerful sought to impose on his nation. He clarified the terms of the struggle with his heroic example. He reminds despairing liberals, “We are still here.”

The great American film-maker died this week, leaving behind a body of work unmatched in its seductive strangeness and transcendent mystery. We put it in order

It is one of life’s eternal mysteries that for the last two decades of his life, no one was willing to fund another feature by America’s greatest film-maker of the time. Almost as much of a mystery was his final completed feature: the evil twin of his previous film, Mulholland Drive. As Laura Dern’s hexed actor segues into the character she is playing, this digitally shot rampage down Hollywood’s boulevard of broken dreams dials up the narrative fragmentation of his late period. It runs the gamut from inspired camcorder surrealism to making-it-up-as-you-go-along incoherence (which is what it was: Lynch shot without a finished screenplay).

Continue reading...